The Progression of the ARC-AGI Frontier

What we can learn from six years of improvement on Francois Chollet's general intelligence benchmarks

(being weekly post 7 of 52 in the year 2026)

Somewhere in a data center, billions of billions of floating point calculations whir away on a fleet of GPUs, spitting out hundreds of thousands of tokens. The last 100 tokens are formatted and sent to a remote server for grading. A single puzzle has been completed. 119 more to go.

Finally, the result comes back: 84.6%. A new world record for Gemini 3 Deep Think! Has artificial general intelligence been achieved?

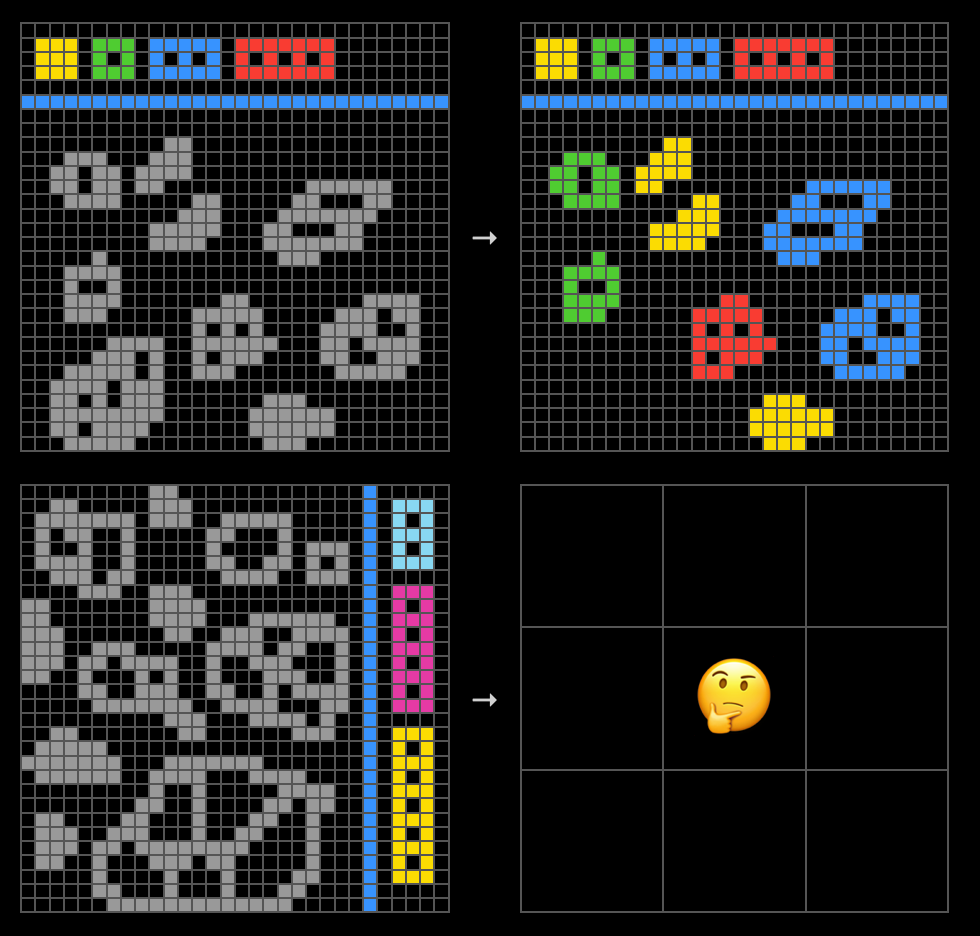

ARC-AGI is a series of benchmarks aimed towards evaluating the intelligence and/or reasoning ability of AI systems via the completion of visual patterns. Since 2019, AI systems have steadily progressed towards solving these tasks, with multiple high scores being published this month, each using a different solution architecture. But what particular approaches have succeeded, and how can we interpret those results?

These questions are answered in three parts:

The history of ARC - starting from the seminal paper On the Measure of Intelligence and continuing through the evolution of the benchmark and key historical solutions

Do we have AGI yet? (probably not) - discussing how we might interpret benchmark results in light of the AGI question

Are base LLMs the best? (so far, often so) - discussing the performance of different solution architectures, and how we might attribute performance gains to different research advancements

Finally, I touch on whether today’s commercial LLMs might grow to become generally intelligent.

Part 1: The history of ARC

2019: ARC is created

In 2019, Keras creator Francois Chollet was concerned by humanity’s lack of progress towards artificial general intelligence (AGI). Disillusioned by the lack of flexibility in contemporary AI systems, Chollet published the paper On the Measure of Intelligence, arguing that better metrics for intelligence would aid in the development of usefully intelligent systems.

He wished to first nail down a definition of intelligence. The paper discussed many existing definitions, eventually arriving at skill-acquisition efficiency - the ability for a person or machine to quickly learn new techniques in new environments and thereby solve new problems.

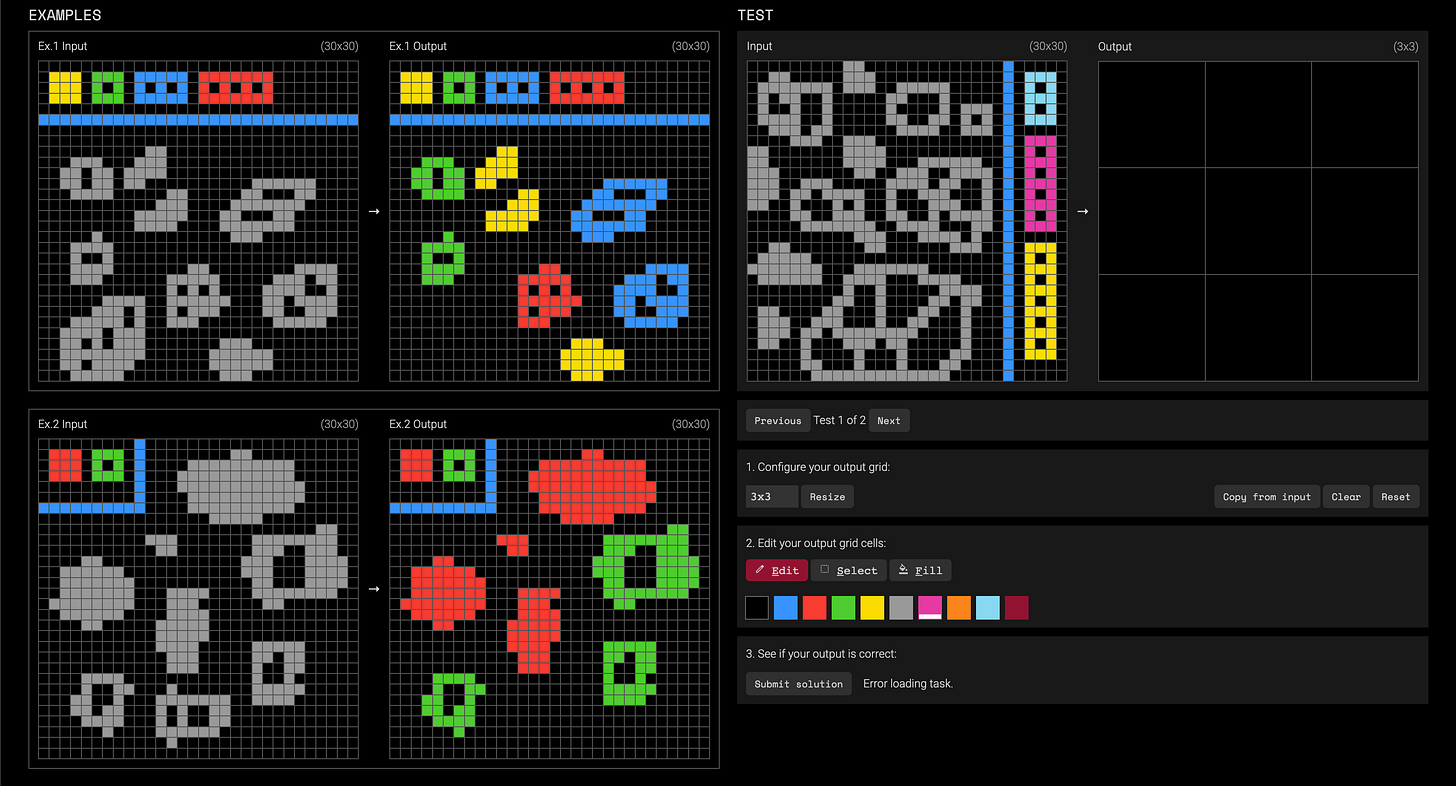

To help researchers measure skill-acquisition efficiency, the paper presented a set of puzzles titled “Abstraction and Reasoning Corpus (ARC).” Each ARC task includes pairs of pixel grids, each pair representing an input and an output. The test taker must determine the pattern between inputs and outputs and apply that pattern to a test puzzle (a lone input grid). For example, the following puzzle requires completion of a symmetrical pattern:

Each task in the dataset is handcrafted to represent a unique human-understandable pattern. If a test-taking machine could cheaply and reliably solve these without training on similar tasks beforehand, that would be a strong signal of its skill-acquisition efficiency and therefore general intelligence.

At the time of the paper’s release, no machine scored well, but commercial LLMs were right around the corner.

2019 - 2024: The rise of commercial LLMs

In 2019 LLMs were still nascent technology, with OpenAI’s GPT-3 model to be completed one year later in 2020 and released as ChatGPT in November 2022. How did this model and its successors fare against ARC?

Surprisingly poorly (though unsurprising for Chollet). Even GPT-4, released March 2023, scored only 7% when presented with textual versions of the problems (source: Jack Cole). And GPT-4o, released mid 2024, achieved only 4.5% (source: ARC leaderboard).

Notably, GPT-4 was OpenAI’s first “vision model,” but it seemed that the model’s new image-processing capabilities did not yield substantial gains on visual reasoning tasks like ARC’s.

This failing stood in contrast to early LLM’s ability to mimic human conversation. Such mimicry was once proposed as a measure of intelligence in Alan Turing’s famous Turing Test. And yet, progress in conversation mimicry soared while progress on ARC stalled.

Alternate ARC approaches show promise

Program search (2020-2023): Chollet first hosted an “ARCathon” competition in 2020, and a pseudonymous “ice cuber” won with a 21% score. Ice cuber’s approach involved no neural networks, and instead used brute-force program-search over a domain-specific language (DSL) of pre-built image-transformation primitives, attempting to compose a sequence of transformations that would faithfully produce the example outputs from the example inputs (source: ARC-icecuber repository).

As competitions continued, brute-force program search solutions remained winning but with diminishing gains. In early 2023, Michael Hodel created an ensemble of past program-search solutions, scoring a 30.5% and capping off the era of program-search domination (source).

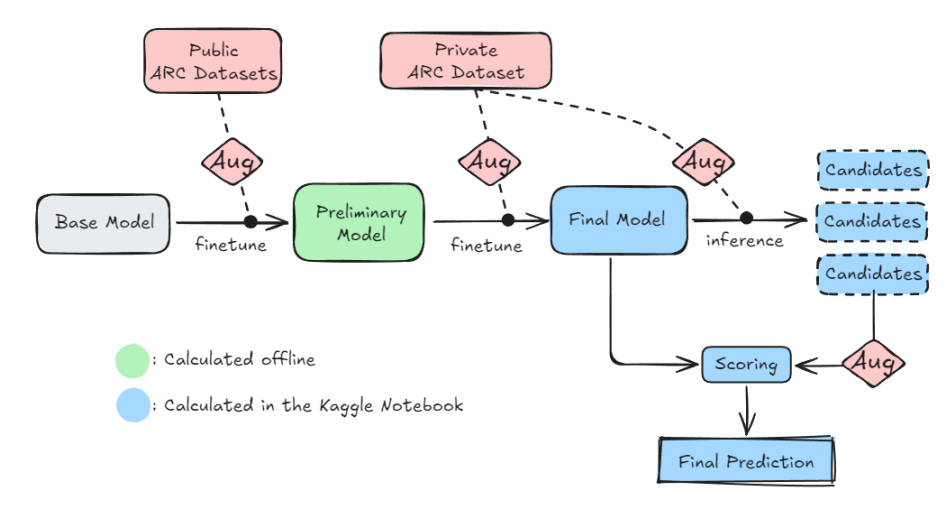

Transformer-based solutions take the lead (late 2023): Then at the 2023 ARCathon, a team named MindsAI shared first place, and soon after recorded a new high score of 33%. MindsAI’s solution is documented in their 2025 paper, and is notable as the first state of the art deep-learning based approach.

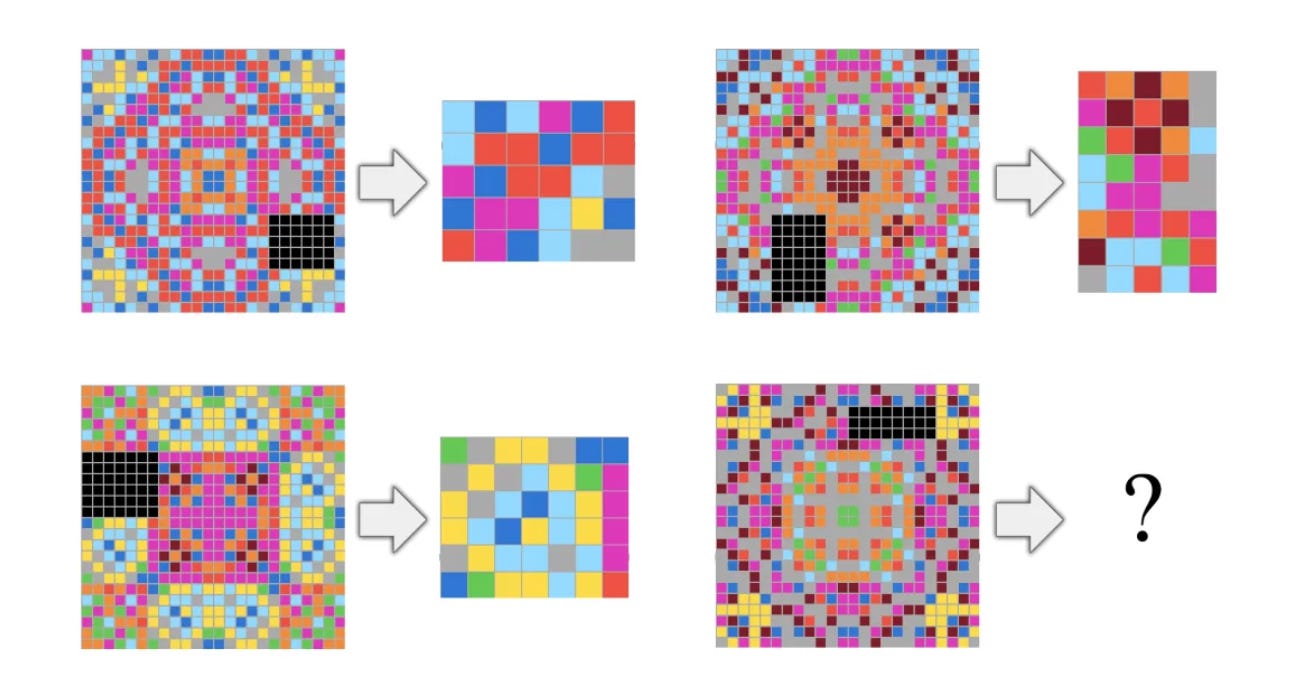

Their solution has three main components:

Pre-training on synthetic and augmented data: They used Michael Hodel’s RE-ARC to create 400,000 ARC-like puzzles for pre-training.

Test-time fine-tuning (TTT): At test time, for each puzzle, they generate a small training dataset based on augmentations of the given input-output pairs (for example, removing one pair, rotating the grids, applying a new color mapping), then they fine-tune the model on that augmented dataset. This was their core innovation, to which they attribute a 300% accuracy boost.

Augment, Inference, Reverse-Augment, Vote (AIRV): This part is very clever in my mind. First they use the same data augmentation engine as above to transform the test input grid into a large number of similar grids (using rotations, color mappings, etc.). Then, they run inference on each transformed grid, collecting a list of results. These results can then be remapped using the inverse of the original transformations, yielding legitimate candidate results. The candidate that received the most “votes” (that was produced the most times across all transformations) is chosen as the winner.

2024: ARC Prize announced

In mid 2024, Chollet teamed up with Zapier founder Mike Knoop to announce the ARC Prize, setting up $1M+ in incentives including a $600K grand prize. To secure the grand prize, a team would need to publish open-source code capable of achieving an 85% success rate on the ARC puzzles, using limited computational resources within a secure internet-free sandbox.

By the end of 2024, MindsAI was in the lead with a 58% scoring solution (an updated version of their previous winning solution). However, they declined to publish their solution’s source code and so did not make it to the podium. First place went instead to “the ARChitects” with a 53.5% score, and the grand prize remained unclaimed.

The ARChitects new deep-learning approach

The ARChitects overall pipeline was similar in form to MindsAI’s, but with different design decisions for many subcomponents (paper). Their candidate generation and selection approaches were novel:

Candidate generation: ARChitects essentially used the AIRV approach described above, but rather than sampling from a model with high temperature in order to create candidate answers, they performed depth-first search over all possible completions, extracting only those whose sampling probability exceeded a certain threshold.

Candidate selection: Their voting system took into account the sampling probability of each candidate across each input transformation.

In sum, they leveraged the sampling probability distribution built into their deep-learning model to a greater degree than past approaches. Still this was not enough to beat the incumbent MindsAI.

June 2024: ARC-AGI-Pub, the new public leaderboard

In parallel to the above contest, the ARC Prize Foundation released a second benchmark and leaderboard for closed-source solutions, allowing players like OpenAI to officially test their models. The public test dataset is “semi-private” - it’s not available on the open internet and therefore shouldn’t make it into any model’s training corpus (an important consideration when testing for “skill acquisition”), however the data is provided publicly at test time, and so could be leaked or trained on by a bad actor. That’s part of why there’s no monetary reward for ARC-AGI-Pub (though AI labs are surely incentivized to do well on this benchmark for PR reasons).

December 2024: O3’s breakthrough

A series of results on ARC-AGI-Pub brought the high-score for unassisted LLMs into the low 30 percents by the end of 2024. Then, a preview version of OpenAI’s O3, an early chain-of-thought enabled reasoning model, achieved an 88% on ARC-AGI-Pub in December 2024 (source: ARC Prize blog). This was a breakthrough result, but came with some important caveats:

The preview model was trained specifically for success on ARC, unlike the later released O3 model which performed worse (source: ARC Prize blog).

O3-preview took a whopping 14 minutes and $4,560 of GPU compute per task, far exceeding the compute allowance of the open-source ARC Prize contest, and far exceeding reasonable estimates of the true cost of solving these small puzzles.

2025 - 2026: Refreshed benchmarks

Still, in 2025 the ARC Prize Foundation wished to counter the recent success of reasoning models, so they released a a new dataset called “ARC-AGI-2” and the old dataset became “ARC-AGI-1”. ARC-AGI-2 looked much like its predecessor:

… but sought to test for capabilities with which reasoning models struggled, such as:

Symbolic interpretation: assigning significance to visual symbols (see image above)

Compositional reasoning: applying multiple rules on top of each other

Contextual rule application: applying rules under specific contexts

(source: launch post)

In tandem, the 2025 ARC Prize was launched with similar prizes and guidelines to the prior year’s. This time around the eventual top score was 24%, indicating that ARC-AGI-2 was indeed a harder benchmark.

Base LLMs see rising success

Despite the low scores on 2025’s ARC Prize, today’s frontier reasoning models continue to notch higher scores at greater efficiencies against the semi-private test set. Just this month, Google announced a massive 84.6% score (at $13/task) for their new Gemini 3 Deep Think model.

Is it over for ARC? Nope, the cycle continues: ARC Prize is already planning their 2026 benchmark, this time with an interactive game format (ARC-AGI-3), to be released March 25th, which will in all likelihood be more difficult for today’s LLMs. You can play the first three example games here.

Part 2: Do we have AGI yet? (probably not)

Is Chollet moving the goalposts with each new benchmark? And is Gemini 3 Deep Think already AGI?

Well, the goalposts are moving, but wouldn’t a general intelligence be capable of following a moving target? Isn’t that exactly what skill acquisition would enable? Concretely, as long as each successive ARC-AGI benchmark is achievable by humans, we can say that failures on the part of machines indicate a lack of general intelligence.

In fact, Chollet’s original paper acknowledges the need for periodic refreshes:

ARC only features 1,000 tasks in total, and there may be some amount of conceptual overlap across many tasks. This could make ARC potentially vulnerable to shortcut strategies that could solve the tasks without featuring intelligence.

[…]

…to mitigate potential vulnerability against such shortcuts, we intend to keep adding new tasks to ARC in the future, possibly by crowd-sourcing them.

What are the specific shortcuts that Chollet might consider disqualifying? The most likely culprit would be directly training on large synthetic datasets that closely mimic the puzzles themselves. Doing so arguably counts as pre-acquiring the skills that are supposed to be acquired at test time. Such pre-training has already been a hallmark of the winning deep-learning strategies since 2023, and is especially prominent in 2025 prize winner NVARC’s solution. Also, we cannot rule out that closed-source model providers like Google might be taking similar approaches as well to improve their results on the public benchmark. Unfortunately, this makes the entire leaderboard harder to interpret.

No AGI until ARC-AGI-n is insta-saturated

A key pattern to observe is whether new ARC-AGI benchmarks saturate immediately. If Gemini 3 Deep Think scores well on ARC-AGI-3 in March, that would indicate the kind of fluid intelligence Chollet was looking for in his original paper, as the model probably hasn’t trained on environments similar to ARC-AGI-3’s games. If instead it takes time for Google and other labs to saturate the benchmark, we will be left wondering whether the gain is from general intelligence abilities, or from pre-trained skills that are aimed at beating the benchmark.

Part 3: Are base LLMs the best? (so far, often so)

Which methods are most successful against ARC, and which are most promising? Firstly, to define success…

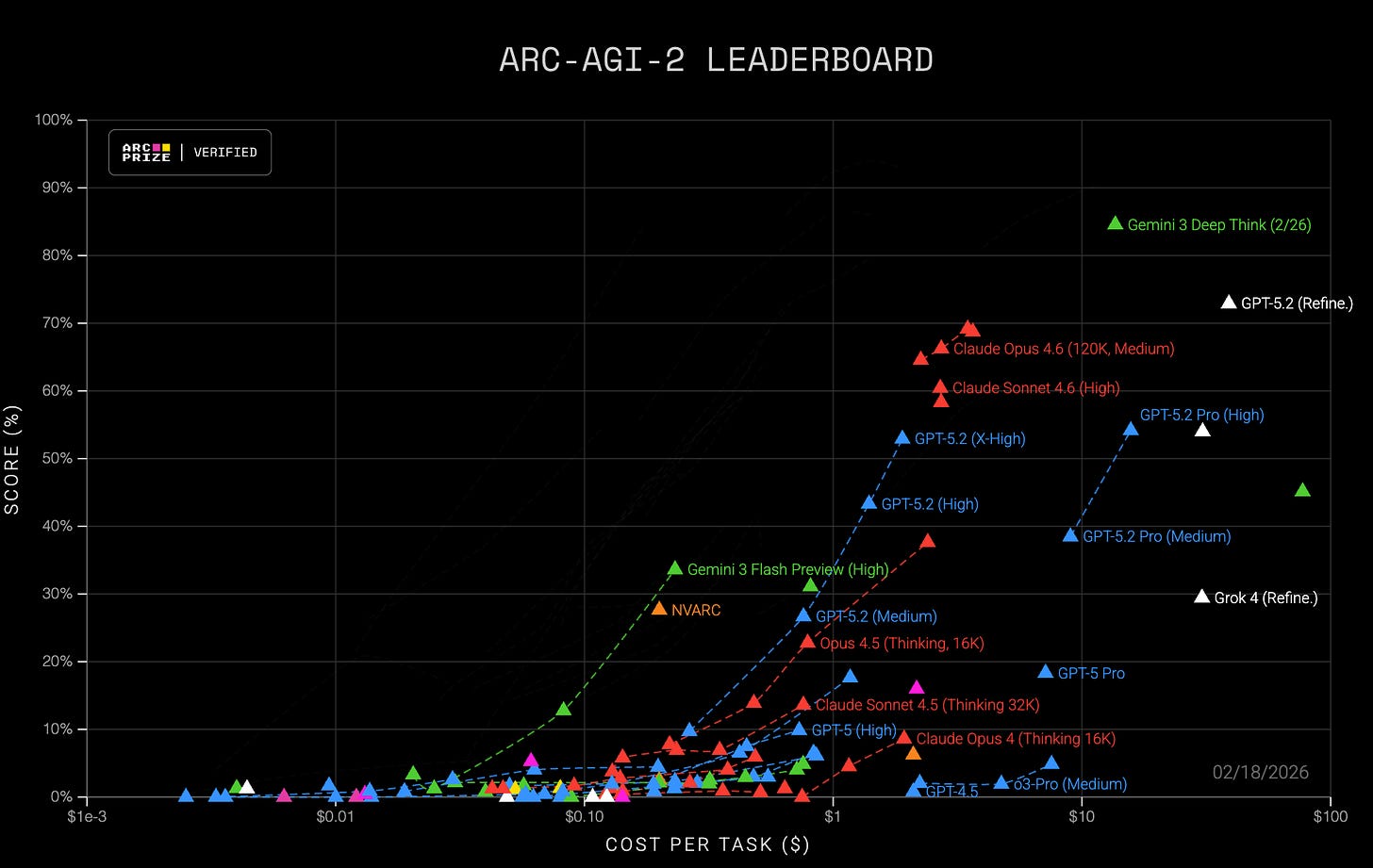

The ARC leaderboards show a Pareto frontier between cost and score, and any submission along that frontier of low costs and high scores can be considered successful. What trends do we see?

Frontier trends

The ARC-AGI frontier has vacillated between different solution architectures - the early 2020s saw search-based program synthesis winning, while recent years saw chain-of-thought/reasoning LLMs pull ahead using transduction (producing the output grid directly instead of producing a program that produces the grid)… just look at how much of the frontier in the image above is dominated by Google’s green Gemini 3 Flash Preview and Gemini 3 Deep Think.

But even in recent months, we see a variety of architectures neck-and-neck for the frontier. Earlier this month a solution by Johan Land (code) topped the leaderboard with 72.9% on ARC-AGI-2 for $39/task. While this was soon eclipsed by Gemini 3 Deep Think, this solution has its part to play in the overall trends.

Johan Land’s briefly state-of-the-art kitchen-sink solution

Land’s solution involves a complicated pipeline, which works as follows (you can skip this numbered list if you’re satisfied by “it’s complicated”):

In parallel, run a bunch of state-of-the-art reasoning LLMs, some of which are tasked with producing a grid output, and some of which are tasked with code generation.

If there’s sufficient consensus among results produced by the above, then finish (this saves some money)

(if enabled) repeat the above steps using different models

Then run all five of these strategies in parallel

Deep thinking: prompt a model to think especially deeply about the problem before producing its output

Image-based: Feed rendered images to a model, ask for grid output

Hints: Get an LLM to analyze images and produce hints. An LLM uses these hints to produce a grid output.

Structured, object-based thinking: A 3-part pipeline that compels models to describe the objects they see, then describe the transformations between those objects, then finally, in context of all previous answers, produce a grid output.

Codegen: Re-run the codegen aspects from step 1, but with more models runs.

This was truly a “throw everything at the wall and see what sticks” solution, combining lots of raw LLM power with various forms of cognitive scaffolding.

For a brief moment it was the highest-scoring solution out there, surpassing Claude Opus 4.6’s score of 69.2% by 3.7%, though at 11 times the cost. Given the 120 puzzles in the semi-private test suite, Mr. Land spent ~$5K on the test run alone, to say nothing of the costs in developing his methods.

The biggest recent gains came from base LLM capabilities

Gemini 3 Deep Think outperformed Land on both accuracy and cost. Approaches with more scaffolding and/or symbolic reasoning, like Land’s, have occasionally reached the frontier, but they usually represent modest gains over incumbent transduction-based approaches, while incurring larger costs. Every approach at the top of the current public leaderboard heavily relies on LLMs even when combined with scaffolding, and improvements in the underlying models seem to cause improvements across the board. This suggests that a large amount of progress towards solving ARC (at least on the closed-source end) is due to advancements in LLMs.

Is this bad news for the ARC Prize Foundation’s mission to support novel research? Perhaps, but they have a few facts working in their favor. Firstly, LLMs did see meaningful algorithmic improvements over recent years - OpenAI’s O1/O3 models, for example, introduced the chain-of-thought reasoning approach that led to huge gains on ARC and many other benchmarks. Secondly, for the actual ARC Prize, which requires open-source models to run on limited hardware, each year’s winners have presented solutions with meaningful complexity outside of the LLMs that they leverage.

A possible synthesis of these facts: at smaller cost scales, independent researchers are incentivized to explore a variety of novel approaches, and these approaches beat out simpler LLM-based approaches and push the research frontier forward. At larger cost scales, submissions become too expensive for independent researchers, except for the occasional tech Senior Vice President (Johan Land), and the charts become dominated by big labs whose primary motive is to showcase their models as standalone products.

Where does program synthesis fit in?

A recent twitter post from Chollet reads:

I believe that program synthesis will solve reasoning. And I believe that deep learning will solve program synthesis (by guiding a discrete program search process).

But I don't think you can go all that far with just prompting a LLM to generate end-to-end Python programs (even with a verification step and many samples). That won't scale to very long programs.

Chollet has long been an advocate for program synthesis, and in January 2025 he and Knoop founded NDEA, a research lab building “AI systems that blend intuitive pattern recognition and formal reasoning into a unified architecture.”

As suggested by the tweet above, the architecture he wishes to build would not be the kind of LLM-assisted program-synthesis approach that Ryan Greenblatt used to top the ARC public leaderboards in mid-2024, which we see repurposed as a sub-component of Johan Land’s pipeline above - though by all appearances, such architectures are close to his vision. NDEA has not published anything yet, so we’ll have to wait and see how their approach differs.

However, the current frontier of ARC-AGI-2 submissions all use direct transduction without program synthesis, so it would be impressive if NDEA could present a program-synthesis architecture that’s competitive on past or future ARC benchmarks.

Will the LLMs generalize?

The ARC-AGI frontier has been populated by a wide variety of cognitive architectures, but for now is dominated by commercial LLMs - the same systems that answer our questions and write our code. Seeing whether these systems succeed immediately on the novel ARC-AGI-3 tasks will be a good test of their general intelligence abilities.

A key open question is whether commercial LLMs will grow to succeed at ARC-AGI-3 and subsequent versions. Per the ARC Prize website, “AGI [is] still unsolved. New ideas [are] needed.” But Dario Amodei, CEO of Anthropic, would disagree. In a recent interview with Dwarkesh Patel he indicated that he expects Anthropic’s training plan to scale to fully generalized intelligence (at least in domains that are operable by text). I’ll leave with his quote:

…all the cleverness, all the techniques, all the “we need a new method to do something”, that doesn’t matter very much. There are only a few things that matter.

[…]

In fact, I would point to the history in ML of people coming up with things that are barriers that end up kind of dissolving within the big blob of compute. People talked about, “How do your models keep track of nouns and verbs?” “They can understand syntactically, but they can’t understand semantically? It’s only statistical correlations.” “You can’t understand a paragraph, you can’t understand a word. There’s reasoning, you can’t do reasoning.” But then suddenly it turns out you can do code and math very well.

[…]

I think we may get to the point in a year or two where the models can just do [software engineering] end-to-end. That’s a whole task. That’s a whole sphere of human activity that we’re just saying models can do now.